- for SLR owners -

aperture

shutter speed

stop

exposure

metering

blur

depth of field

conclusion

top

The

aperture

When we step out of

the dark into the sunlight, we usually blink our eyes. Our pupils are

wide open in the dark and it takes a moment to adjust them to a small

aperture. In fact we react very fast to changing light conditions. So

fast in fact that most of the time we're not even aware of it.

the pupil in the iris of my eye

In photography we

are continuously dealing with the amount of light that is avalaible to

us. And more specifically with the difference between the dark

and light areas of the scene we want to record. This difference we call

contrast.

In our eye we regulate

the the amount of light that reaches our retina with the pupil, the round

opening in the iris that gets larger or smaller. With a camera we have

two devices to regulate the amount of light. The aperture and the

shutter speed.

To expose our film correctly, there is a third factor: the film

speed.

aperture

The aperture, or diaphragm, or lens opening is also a round opening we can make larger or smaller. This is done with thin metal leaves that shift over each other. It is located in the middle of the lens.

aperture control ring of a classic Nikon

With classic cameras we can see it opening and closing, when we look in the lens, while we turn the aperture ring. On these cameras we can set the aperture at certain fixed positions. The ring clicks in these settings as we turn it.

![]()

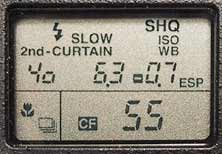

display with aperture and shutter speed

display of a digital camera

Modern cameras have data panels and touch dials. These controls are nice, clean and practical. Unfortunately the direct relation between control and function is lost. This makes it more difficult to master these functions.

To each setting there is a corresponding number that indicates the opening. These numbers put next to each other form the aperture range. The first number is the largest aperture of that specific lens. The range goes as follows:

aperture range

1.4 - 2.0 - 2.8 - 4 - 5.6 - 8 - 11 - 16 - 22 - 32

We will not see all

of these numbers on the lens barrel or in the display. Sometimes there

will be intermediate settings. The widest aperture may well be a intermediate

setting, 3.5 for a zoom lens for example or 1.7 for a standard prime lens.

This is all very nice but not very important.

What is important, is:

1 - To know that these numbers form a logarithmic range, because they are derived from the area of a circle.

2 - Never to

forget that this area is doubled or halved with each next

setting. So opening the aperture one number from one lens opening to the

next one setting larger, the opening gets twice as wide and will

let through twice the amount of light. From one lens opening to

the next smaller lens opening the area is halved and thus the

amount of light passing through the opening is halved.

3 - A low aperture number is a large aperture. A

high number is a small aperture.

Confused? Not when

we speak and think of lens opening instead of diaphragm or aperture.

A large lens opening or a

small opening is immediately clear.

Top

The shutter

speed

With SLR's,

single lens reflexes, the aperture is located in the lens. The shutter

is located in the camera body, in front of the film. We can see it when

we take off the lens and look into the body, behind the mirror. -Please

do not ever touch the mirror-. We can also see it when we change film

and we open the camera back. With the film removed we look directly at

the rubber shutter curtains or the metal shutter leaves. -Please do not

ever touch these either-.

When we press the shutter release, the shutter curtains or leaves move

very quickly from right to left or from top to bottom. Between the two

curtains or the leaves, an opening or a slit is left open, through which

the light passes onto the film. The film sits directly behind the shutter.

The amount of time the light is let in, is variable. It can be very short: 1/2000 of a second for example. But it can also be rather long. As long as half a second: 1/2 s. That amount of time we call shutter speed. It indicates the amount of time the shutter is left open. The shutter speed numbers put in row form the shutter speed range. It looks like this:

shutter speed range

1/4000 - 1/2000 - 1/1000 - 1/500 - 1/250 - 1/125 - 1/60 - 1/30 - 1/15

- 1/8 - 1/4 - 1/2 - 1 - 2s - 4s - 8s

We have to learn this by heart too, to know what numbers we are looking at in our data display.

shutter speed dial on a classic Nikon F

Modern cameras with

electronic shutter speeds will display intermediate values like 1/90.

This is nice too, but again is not very important at this moment.

What is important is:

1 - To know that these numbers form a directly proportional range, derived from the shutter speed. Which has nothing to do with speed, but with the time our film is left exposed to light coming through the lens.

2 - This amount of time is halved or doubled from one step to the next. (Hey we heard that before.)

3 - A slower

shutter speed doubles the time. And twice the amount

of light will be let in.

A faster shutter speed will halve the time. And will let

in half the amount of light.

Top

A stop

The

step from one shutter speed to the other, faster or slower, is called

a stop. This goes for the aperture also: the step from one opening

to the other is called a stop.

The stop is the unit with which we work and by which count in photography.

Opening one stop means: we open the lens opening from e.g. f

8 to f 5.6. This f indicates the aperture. So we double

the amount of light passing through the lens.

One stop faster means: from e.g. 1/30 s to 1/60 s. The amount of time

the light is let through, is halved. One stop slower means from 1/30 s

to 1/15 s. The amount of time is doubled.

Sometimes for speed we use the letter t; so: t

1/30.

A stop always

means half or double the amount. Of time or

light.

Top

Exposure

The film that is in our camera must be exposed. This will

happen by a combination of shutter speed and aperture. This combination

depends on the amount of light which is available at that moment. And

on the speed of the film in our camera (fast or slow film). And it depends

on the choice we make out of all the posible combinations.

If we make a mistake, for example by letting too much light reach

our film, then the film gets overexposed. When too little light

reaches our film it is called underexposed.

Top

Metering

We measure light with a light meter. In almost all cameras it is integrated.

This meter should know which speed the film in the camera has, in order

to give the correct exposure. So we have to tell the meter the filmspeed.

Most modern cameras will do this for us, it will read the bar code on

the cassette: the DX-code. With older cameras we have to set the film

speed somewhere on the body.

Film speed is now

indicated by an ISO number (formerly: ASA or DIN). A slow speed is 50

ISO (sometimes the notation is: 50/18 ISO, the 18 comes from the older

DIN notation). We call this a slow film.

A fast speed is 800 ISO or higher, we call this a fast film. It is more

sensitive to light.

In black-and-white photography 100 ISO and 400 ISO are mostly used. In

color we also find 200 ISO quite often. With transparency or slide film

the speed is generally somewhat slower: 50 en 100 ISO.

We always meter the

light on our subject. So that means it is the most important part of the

image we are recording. If everything is equally important, then we have

to take care that the difference between the light parts and the dark

parts of the image (the contrast) is not too big. Because if the contrast

is too big, it will not fit on our film. The whites will be too white

and the darker parts will be too dark. This limitation of the material

is called contrast range. Or exposure latitude.The difference between

the lightest and darkest parts we can record on film as a rule can be

no more than 5 stops. With some material it is less.

We always must pay attention to bright objects within our frame. Like

a window, a light, or the sky. They will influence the metering severely.

The light meter will measure the whole frame and will not know at what

it is looking.

A meter basically expects an even distribution of black and white over

the whole image. We all know that this is not the case in reality. Modern

cameras with segment-metering will still not know at what we are pointing

our camera.

So if there are a lot of bright parts in our frame, but they are not our

subject, it is as if our camera is thinking: It is very bright here; my

aperture must be small and I must close my shutter fast. So to avoid that,

we have to take a reading very close to our subject. We have to point

our meter at our subject exclusively. Move in till the subject area fills

our frame exclusively.

Sometimes this is very impractical. Then we can also measure something

that is the average between white and black, in exactly the same light

as our subject. This is called a substitution reading. We use a

gray card for that. This is a card or a plastic board of an exact shade

of gray with a reflectance value right between white and black. Surprisingly

this average is not 50% gray but 18%. So this card is called the 18%

gray card. Metering using the gray card is the most exact way of determining

the exposure, because all meters are designed to calculate exposure for

subjects in reality of this tone.

Top

Blur

The

shutter speed not only determines the duration of the exposure, but it

also has an important impact on our image.

If we take a picture with a fast shutter speed, the image will seem frozen.

Even a speeding car. Which will look as if it is parked in the middle

of the road.

![]()

fast

shutterspeed: everything is frozen

fast

shutterspeed: everything is frozen

![]()

![]()

slow speed: everything in the image is blurred.

slow speed: everything in the image is blurred.

But if on the other hand we take a picture with a slow shutter speed,

everything in our image will be blurred. First of all it is very difficult

to hold our camera steady. And if something in the frame moves, it will

be blurred in the picture.

Top

Depth-of-field

Like the shutter speed which not only determines exposure but also the

appearance of our image, also the aperture has an important 'other' function.

The aperture determines how much in the frame is sharp in front of, and

behind, the point where we focused.

The zone where things are sharp (more accurately: sharp enough) in front

and behind our focusing point is called the depth of field.

The bigger the lens opening is, the more shallow the zone in front and

behind our point of focus is.

Shallow depth of field. With a large lens opening only the plane

where we focus is sharp:

foreground and background remain unsharp.

In a landscape or architecture we usually want a greater depth of

field: a small lens opening.

With a small opening the forground as well as the background are sufficiently

sharp.

This might be the single most important reason pictures do not turn out

as we expected them on the moment we took the photo. All of a sudden there

is a tree growing out of uncle Bill's head. Or antlers protrude out of

his ears. And when we took it we never saw all of this. Our frame was

so quiet: nothing distracted the view. When we pressed the shutter there

were no tree nor antlers in sight. The explanation: we focus at the largest

opening of our lens. The viewfinder is all serene. Only the focus point

is sharp. In front nothing, in the back nothing. But then the program

kicks in: it closes the aperture. Our camera takes over. It is thinking

for us. It determines opening and speed. And in this case with the antlers

there happens to be a lot of light so the aperture gets closed. And here

comes the tree or here come the antlers within the depth of field.

So use the P of program for Panic only.

In all other cases, do not let our cameras do the thinking.

Think for

yourself!

The

solution for a better image: think for yourself. Do not let your camera

decide how things will look in your picture.

If movement is the issue, - wether it has to move or stand still: choose your shutter speed first.

If sharpness

is the issue, - a greater depth of field in case of a landscape, or a

very shallow depth of field in case of a portrait in front of a very disturbing

background, choose your aperture first.

Top

Still

confused? Have a look at a page where I explain the

relation between aperture and shutter speed with a glass under a tap

- the old bucket and tap analogy.

Want more? Go to the links page to

online and offline lessons (now over 250 and counting)

Sorry, some of the comment on that page is in dutch at the moment.

It still is an enormous amount of knowledge you can find through these

links.

Im not a native speaker in english - you may have guessed ;-) -

so: if you have any remark on this article,

please sent me a mail